Stop 1

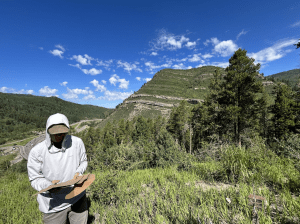

After piling into our cars for a short two minute drive, we arrived at our first stop: the base of a mountain in the town of Minturn, Colorado. We were given a topographic map, clipboard, and set off to bushwhack our way up the mountain, stopping part way to observe some sedimentary features such as mudcracks and ripples. We finally arrived at a flat clearing at the top of the trail and parked our belongings, eager to learn what the mysterious “rule of V’s” was, as it was found on many of our bingo cards.

This overlook displayed a clear view of the town below, and most importantly, the exposed bedrock on the face of mountains surrounding us. We began by observing the surrounding exposure, noticing a similar appearance and structure of the rocks, even across the valley. Stewart Williams, our resident structural geologist, led a discussion on key principles of structure and field mapping – strike and dip. Strike is a line of constant elevation of a rock layer, and dip is the angle and direction the rock faces relative to horizontal. We noticed that the dip in all of the units visible was consistent, and seemed to shape the topography of some of the hills in the region. Applying these concepts to field mapping, we learned about the “rule of V’s”, where contacts between rock units ‘V’ in the direction they dip.

The rock contacts that were exposed and mapped in the Minturn area were as follows; from youngest to oldest is the Pennsylvanian Minturn Formation, divided in to middle and lower members, the Pennsylvanian Belden Formation, Mississippian Leadville Formation, Paleozoic Undifferentiated and Precambrian Crystalline Basement.

From this first stop we were able to map the Pennsylvanian Minturn Middle and the Pennsylvanian Minturn Lower. This was accomplished by drawing solid lines for the visible contacts, and dashed lines of uncertainty where extrapolations were made; the goal for this day was to draw a geologic bedrock map of all the units, and become confident enough to fill in the dashed lines. As scientists, to become more confident in a conclusion, more data is necessary. This is what stops two and three accomplished.

Stop 2

Driving approximately 15 minutes along a thin windy road, we reached the Cross Creek Trail. We hiked for approximately three minutes before reaching our destination. This stop was an overlook with visibly very different geologic units. Taking a quick look at the rocks beneath our feet, we immediately discovered the rock to be igneous, in particular a granite, due to its coarse grained, crystalline texture. We determined this rock to be the Precambrian Crystalline Basement and mapped this area onto our topographic maps. The mountain we faced also showed the Paleozoic Undifferentiated unit which appeared red in color. In addition to expanding our field map with the two newly visible layers, we observed glacial features in this area including a roche moutonnée, glacial striations, and a lateral moraine.

Stop 3

Finally, after a much longer trek, we reached the top of the mountain and the flagpole overlook. Here we were able to fill in the remaining gaps in our geologic map and be fully confident in our interpretation of the bedrock in the region.

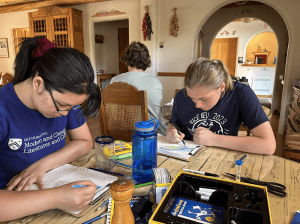

Back at the hotel, after descending the mountain, we colored in our geologic maps to indicate the different units and compared them amongst our peers. Mapping is a very important skill in the geological sciences; it can be useful for providing context to research in an area, mapping mining potential, understanding hazards, construction, and so much more. This is why getting exposed to this skill was not only fun, but also important!

Written by Claire Rubin